The long hallway of a career in photography can seem endless. Occasionally, the lights are out, and you barely find your way. There are windows, perhaps, to peer through, and some doorways to walk through–hopefully.

One huge door for me was my first real, honest-to-goodness assignment for the National Geographic, the actual yellow border magazine. It was back, as they say, in the day. It was the late 80’s, and, spurred by Lee Iacocca’s fund raising, the main buildings of Ellis Island were being saved, polished up and made museum-ready. The abandoned pieces of the island remained so. Just last week, in 1954, the island officially wrapped its mission as America’s gateway. I noted that anniversary by doing a little Instagram series on the passing of the place into disuse.

Geographic had assigned another shooter, who either bailed on the job from an onset of common sense, or got reassigned to do something more grand. Dunno which. The Ellis effort I was commissioned to make was, for them, at that time, a small one. I think I was given six or so weeks. Six weeks! To a guy who had gotten used to five days being a major cover story! Holy shit! Nirvana! The yellow border gleamed in the distance, Oz-like and fanciful. Elysium beckoned.

My rapture was only slightly dimmed by the prospect of shooting this in November and December, in the middle of the NY harbor, and waking up at 3am every morning and transiting out to the island in the glacial gloom and numbing frost of winter. Which of course only deepened as I roamed into dark corridors, places awash in the dreams and despair of many a forgotten soul. I would peer about, looking for a glimmer of early sun that might slice through the place and banish the ghosts.

My fervor didn’t even pale in the face of the finances of this epic effort I was about to make. Being a fledgling Nat Geo photog, a runt in the litter of possible freelancers, I was offered an introductory day rate of $250 per day. There was a Darwinian aspect to all of this–if you couldn’t cut it, well, they wouldn’t have wasted much dough on you. If you indeed emerged from the Thunderdome of your first assignments, only then would your prospects brighten. I was such nameless cannon fodder at that point, my editor barely spoke to me during the entire deal. I’m speaking straight here. I think I had maybe two conversations with him during the whole gig, and they were relatively unpleasant for me, as he was utterly indifferent to my sweat stained, desperate efforts.

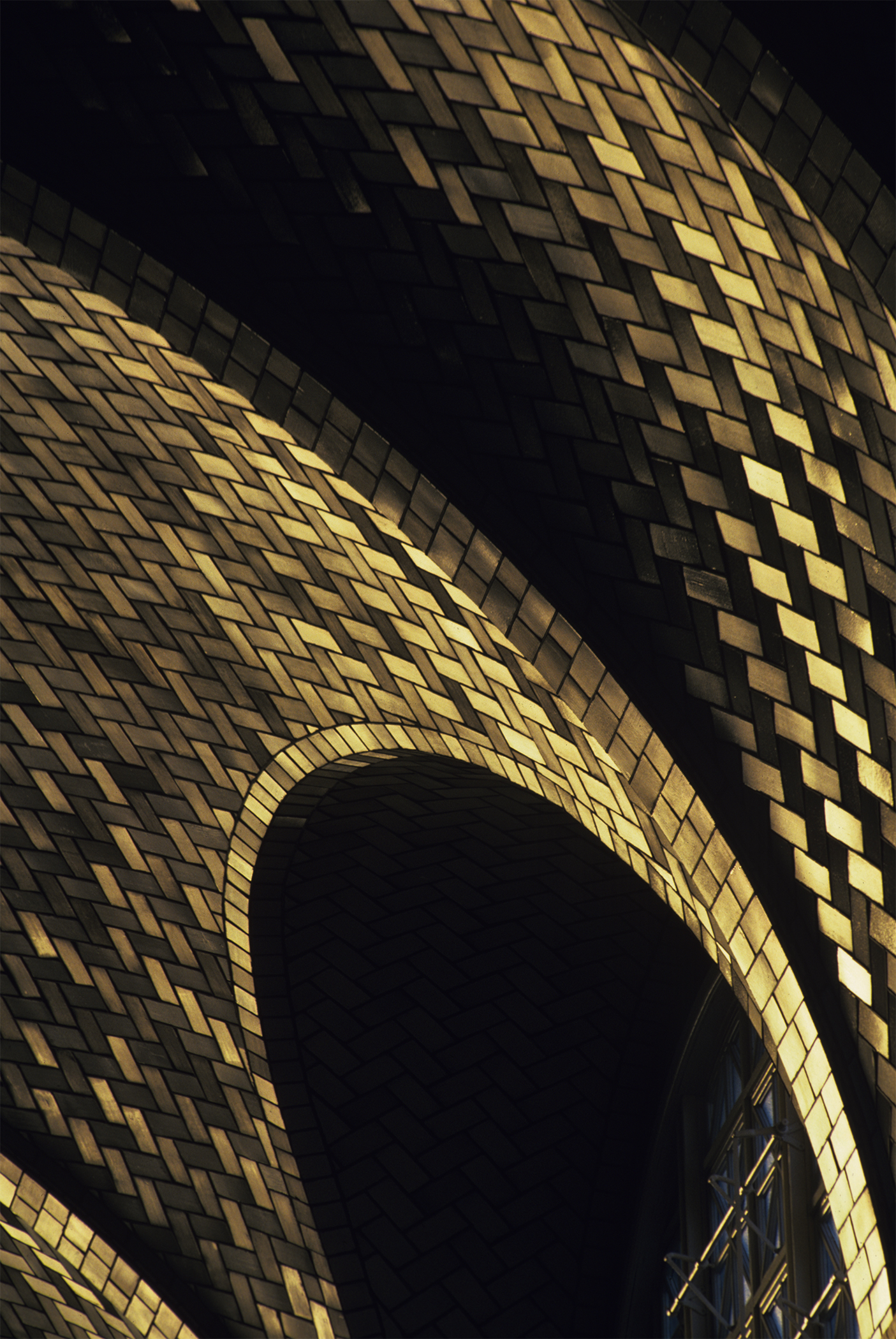

I knew one of the reasons I had been assigned was that I was NY based, and knew how to work the city as a photog. I had to light the whole damn main building of the island as the centerpiece of the coverage, which required the services of most of the rental Speedotron packs in New York City. They in turn required their own damn generator truck, as the building was a construction shell at the time. Which meant I had to find the foreman on the job, and give him a grand, cash. Sure, you can bring your truck out here!

Lighting this building was one of the more miserable tasks one can imagine as a shooter. Power problems, blown packs, differing trigger voltages amongst the units, three ground based camera positions, triggering flashes from the air with late 80’s radio technology. Sheesh. Thought I would just about die outright, or be assassinated by my assistants, who were making the princely sum of, as I recall, $125 a day. Grueling. Shoot sunrise. Run film to the lab. Wait for clip tests. Judge film, and process. Realize failure. Go back to island. Adjust lighting. Shoot sunset. Run film to lab. Do clip tests. Process based on results. Weep while you loupe your film. Sleep for three hours. Head to island. Adjust lights. Repeat process. For three days.

I survived. Barely. It was nutty. Woe to any other photog who might have wished to hire large power packs that week in NY. I had about 50-60 of ’em out there. Over 100,000 watt seconds, easy. When the place went up, you could see it from Brooklyn or Jersey. Try that now, there’d most likely be SWAT teams all over you.

My editor never called me at the end of it. Tom Kennedy, the DOP of Nat Geo, did, though, and this is where the intersection of a photographer and a good picture editor has long standing repercussions. Among other things, he simply said, “nice job.” It was all I needed to hear to get to the end of that long, dark hallway.

More tk….

Great story, and as always, great shots!

Ah… The good old days. Reciprocity failure and all.

There’s a saying that sooner or later everythingvis either laughed at or forgotten. I don’t know that’s necessarily true, but thanks for the smile.

Here’s a different lighting story for you…of sorts: Biology student, working in the wilds of eastern Quebec. We were doing an environmental assessment of spraying a new pesticide for spruce budworm. My boss, D. was a great guy. Very knowledgeable, very easy going. One night the two of us were out in an absolutely torrential downpour, with a flashlight that worked if you held it level but shut off if you turned it down so you could actually see what you were doing, collecting these tiny flies out of plastic buckets with tweezers and putting them into small vials of alcohol. D. turned to me at one point and said, “You know, Mike…sometimes I wonder why I love this f___ing job.” I thought, “Yup. That sums it up right there. You do it because you can’t imagine being anywhere else. Wouldn’t be right.”

Mike.

The best stories come out of the worst experiences. Nobody wants to hear how everything worked out as planned. With that realization, I almost never complain about grand misadventures…only the mildly annoying ones.

Great Story, Like the new website

I remember when I started out in photography, before I ever popped a flash, a very well known photographer pointed you out in a crowd and said, “that’s Joe McNally, he lit Ellis Island.” I replied, “I’m surprised he is here and not in jail..” She looked at me like I had three heads. I thought you were a crazy man who liked to play with matches.

Hey Tom….Yep, jail time could have been a result, I guess! Wouldn’t want to do it now, though with new tech in flash and radios, it’d be a helluva lot easier. Hope you’re good, thanks for stopping by the blog. Joe

This has and always will be some of my most favorite work of yours! All of your work has been fantastic and inspiring. We have a bit of history between us but as your student and for your mentorship and encouragement, yes Im bias. Your continued efforts to share your vision, your knowledge, respect for your subjects and your sense of humor will always be a driving force to improve my own knowledge and image quality. have not always succeeded but have always learned by the experience. More than once I have said with my inside voice how would Joe have approached this??? Thank’s for being you!!!! as always! Cheer’s!!!

Adversity builds character.

If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again… A great story on the best way to learn. Can you imagine being given 6 weeks to shoot Ellis Island nowadays? Even the Nat Geo is cutting back….

You are a tribute to determination – üben, üben, üben – over, over, over

I find long hallways shots amazing yet a bit horror like. For me, it is scary but creative!

Joe this brilliant. Looks like it was photographed yesterday. Great job. H.

Wow – this images are so powerful and heavy, under the burden of the whole, very active, history they went through. And this is how they tell the story now – waiting to be discovered by someone who wants to see and listen.

Wow! Powerful story. Love the light and contrast of the inside and outside on your 5th photo!

If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again… A great story on the best way to learn.